How To Overcome Writer’s Block

What Is Writer’s Block?

Writer’s block is the kryptonite to a writer’s superpower—creativity. Have you ever found yourself staring at a blank page, unable to write? Perhaps you feel paralyzed by fear or unable to begin the process. Perhaps you move your hands to the keyboard, or lift your pencil to the page time and time again, only to pull them away, thinking hmm, why won’t the words just flow? Writer’s block happens to nearly every writer; it’s inevitable. Writer’s block is the inability to freely dive into writing and the feeling that whatever words come from your fingertips aren’t worth writing in the first place or won’t be good enough. The bad news? You’ve diagnosed yourself with writer’s block. But the good news? It’s treatable and an obstacle you can definitely overcome.

Hello readers and writerly friends!

If you’re a returning reader, welcome back and if you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by! In this blog post, we’re discussing writer’s block and all it encompasses, how to overcome it, and how to keep it from interfering with your creativity. There's thousands of other posts and articles out there that explain this topic, to be sure. But I am diving deep and explaining my own personal experience with writer’s block, how I overcame it, and how you can too. This post will deconstruct the nebulous concept of writer’s block and break it down into easily understandable symptoms and actionable and effective steps for curing these symptoms. This post is a longer one, so grab your coffee, tea, and your notepad and let’s get into it!

What Is Writer’s Block?

Writer’s block is the kryptonite to a writer’s superpower—creativity. Have you ever found yourself staring at a blank page, unable to write? Perhaps you feel paralyzed by fear or unable to begin the process. Perhaps you move your hands to the keyboard, or lift your pencil to the page time and time again, only to pull them away, thinking hmm, why won’t the words just flow? Writer’s block happens to nearly every writer; it’s inevitable. Writer’s block is the inability to freely dive into writing and the feeling that whatever words come from your fingertips aren’t worth writing in the first place or won’t be good enough.

What Does Writer’s Block Look Like?

It looks like a writer hunched over their keyboard or notebook with a furrow in their brow, a purse in their lips, and a blank page before them. It looks like a lack of motivation, inspiration, or consistency. It looks like notes and binders and word documents galore, but no completed book or short story to tie them all together. It looks like an untouched laptop or notepad gathering dust in the corner. Writer’s block presents itself differently for every writer, but the symptoms are often the same. The bad news? You’ve diagnosed yourself with writer’s block. But the good news? It’s treatable and an obstacle you can definitely overcome.

What causes writer’s block?

Writer’s block, while perhaps not a proper medical condition, is a creative hurdle that stops many writers in their tracks. It stems from inexperience, underdeveloped ideas, burnout, a lack of enthusiasm, motivation, or inspiration, fear of rejection or a feeling of inadequacy when it comes to a writer’s own abilities, and maintaining a lifestyle that does not support the habit of writing. Seasoned and aspiring writers alike can suffer from this roadblock in the creative process, but with time, practice, and perseverance, writers can push past this block and eventually leave it in the dust altogether.

A woman working on a Macbook. Photo by Elisa Ventur.

Why Am I Experiencing Writer’s Block?

You may find the answer to this question below:

Inexperience: Many novice writers do not know where to begin. They don’t know how to write a story, let alone develop and format a book. They don’t know the rules of writing and that inexperience can hold them back from unleashing their creative potential. If you want to be a writer, and a successful one at that, you must educate yourself on writing tools, best practices, and storytelling as an artform. This is the foundation of being an effective and knowledgeable writer. Read books about writing, take classes and attend workshops to build your skills with practice and feedback.

Underdeveloped ideas: Many writers find themselves unable to start writing because the ideas they want to write from are not fully developed. Brainstorming and research are crucial parts of the writing process. Writing from a vague idea is much, much harder than writing from a fully-realized idea. Depending on the genre you’re writing from, take all aspects of the story and cultivate them so they can grow from a budding seed of inspiration to a blossoming concept. For example, if you’re writing a fantasy story, write detailed descriptions of all the characters, settings, world cultures, religions, and histories, timelines, and events. These wordy descriptions will likely not make it into your draft, but they will serve as notes for you to expand and refine your ideas as you write. If you can see it so clearly in your mind’s eye, then you can write from it as if you were really looking at your main characters in their world, with your own two eyes.

Lack of enthusiasm: Some writers suffer from a lack of enthusiasm about what they’re writing. This can be a difficult hurdle to overcome especially if you write for work and don’t have much of a choice in the subject matter. For those who fall into this category, you have three choices: make some kind of personal connection to the subject matter, or find a new writing job, or write for pleasure instead. For those who have an idea they really like, but feel disconnected from it or as if they don’t know enough about the topic to write on it, go back to the Inexperience bullet point. Educate yourself on the topic thoroughly enough that you can confidently and accurately write about it without feeling like you’re writing in the dark.

Lack of motivation: Many writers feel a lack of motivation when it comes to writing. This symptom of writer’s block can be one of the hardest to push past. Writers who feel unmotivated should take a realistic look at their lives and consider why they may feel that lack of motivation. Do you feel like writing at all? Do you enjoy writing? Do you enjoy storytelling and developing ideas? Do you enjoy making connections with others and sharing experiences? Do you enjoy bringing an idea to life? If any of your answers to these questions were a no, why? Why do you dislike any of these steps?

If you found yourself saying no, why are you writing —or not writing —in the first place? Why label yourself as a writer, if it's not something you actually want to do? Many writers never end up writing a book, but they don this title and put immense pressure on themselves to engage in an activity that truly doesn’t resonate with themselves. Dig deep and determine if you want to write, why you want to write, and why you are a writer. This why is your reason for doing what you do and it’s going to help you shift your mindset in a big way. If writing is your passion and purpose and being a writer is part of your identity, it will help excite and motivate you to practice writing, because it's what you do. Find your personal connection to writing and take it with you into every writing session.

Lack of inspiration: Many people who want to write a book feel as if they have nothing to write about. While a strong feeling, this idea couldn’t be farther from the truth. Every single person has a unique perspective and worldview. Every person has a unique experience. No two lives are identical and in turn, no two stories are the same. Your unique existence is valid and so is your story. If you feel like you don’t have a story or idea to write about, write from real life. Write from your experiences and memories. If you don’t want to write about your personal experiences, write fictional stories that you wish were true about your life. Go back to the Inexperience and Underdeveloped Ideas bullet points and follow those steps. Read other books from the genres you want to write from. Research topics, themes, and ideas, then develop them further into elements you can craft a story from. I like to think the writing process is like building sand castles on the beach —you have billions of grains of sand to work from, but for the castle to take shape, you must sculpt, carve, mold, chisel, and join those grains together. You must work those grains of sand until they form the shape you’re going for.

Diagnosing & Treating Writer’s Block. Graphic by Payton Hayes.

Fear of rejection: Many writers struggle with the fear of rejection whether they are aware of this or not. It comes from a combination of Inexperience, Underdeveloped Ideas, and a low self esteem as a writer. These writers may feel confidence in other areas of their lives —they may do well in school or their jobs, they may feel confidence in their physical appearances, they may be aware of other activities they excel at, but when it comes to writing, they don’t believe in themselves or their abilities. The key to overcoming this struggle is practice. Practice, practice, practice. For many writers, the process of writing is very personal and tied closely to their identity. For this reason, it can be difficult for writers to put themselves and their work out there. However, this can be one of the most freeing experiences and is vital to your growth as a writer. When I started seriously writing, I kept my fantasy stories close to my heart. I never let my friends or family read them because I didn’t want them to actually know what my writing was like, for better or worse. They knew I was a writer, but they didn’t know if I was a good or bad writer, and I clung to that uncertainty. I didn’t put my writing online or allow others to read it until much, much later, when I was in college and was somewhat forced to let others into my thoughts, emotions, and written words. From discussion posts in my online courses to writing workshops and critiques in my creative writing classes, to instructor feedback, I was required to put my writing out there, in some form or another.

What I came to realize was that I should have done this much, much sooner. I would have never broken out of my shell as a writer and a person, had I not been vulnerable and put my work out into the world for others to see, read, like, dislike, criticize, judge, compliment, and tear apart. I was terrified that someone would read my stories and think wow, this is truly poor writing. The reality is that any artform is subjective. We hear this a lot when it comes to visual art, but the same is true for writing. Subjective means “based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions” and when it comes to writing, this means readers will bring their own unique perspectives, worldviews, emotions, experiences, and opinions into the work, whether they are aware of it or not. There is nothing writers can do to stop readers from doing this, and they shouldn’t try to. As a writer, you must allow this fact of life to free you from the confines of wanting to please everyone. Allow yourself to let go of the desire to control other people’s opinions and interpretations of your work. It’s an impossibly unrealistic, unattainable, and unhealthy expectation. Whenever I find myself worrying over how others will react to my writing, I try to remember two things: Buddhism and peaches.

Let me explain.

Look, I’m not a Buddhist and I’m not telling you to convert to Buddhism. However Buddhists do practice the art of surrender. This concept is based on letting go of what one cannot control. You cannot control how others react to your writing. You cannot make them like it. You cannot please every single person with your writing, so just let this go. One of my favorite quotes is from Dita Von Teese who said, “You can be the ripest, juiciest, peach in the world, and there’s still going to be somebody who hates peaches.” There will always be someone who doesn’t like peaches and there will always be someone who can find something they don’t like about your writing. Free yourself from the desire to be liked by everyone, by being okay with rejection. Embrace it. Allow yourself to be disliked, criticized, and unaccepted. Allow yourself to produce bad writing. Allow yourself to fail. By doing this, you remove the pressure to be perfect and allow yourself to be. You allow yourself to write, no matter what comes of it. You allow yourself to grow as a writer and a person.

Writing conducive lifestyle: Many writers have a hard time writing because they do not lead a life that aligns with being a writer. To be a writer, you must have time to dedicate to reading, researching, studying, writing, editing, and honing your skills. Being a writer in practice rather than name, is more than just writing. To be a writer, you must live a life that supports the regular practice of writing and all that process entails. Writing is not only an activity, it is a lifestyle and a long-term practice. It takes years of dedication, consistency, and practice to result in expert, well-honed writing skills. If you have children or a busy life, you may find it quite difficult to carve out time to write, but it is paramount to being a good writer, let alone finding success in writing. If you answered the questions in the Lack of motivation bullet point, then by now, you should know whether or not you really want to continue writing. If the answer is no, you should probably look into something else. However, if you do, then your next objective is to set aside time every day to improve your writing. Make this a realistic and attainable goal and track your progress as you go. Start out simple and ensure your path is the one of least resistance from both yourself and others in your life.

How To Defeat Writer’s Block. Graphic by Payton Hayes.

How Do I Overcome Writer’s Block?

If you read through those lengthy bullet points, then by now, you know what must be done. You know what writer’s block is, what it looks like, how it affects writers, where it comes from. Now that you understand writer’s block, it is time to take action. I’ve listed several ways you can combat writer’s block. Practicing these steps will help you build the muscles you need to defeat writer's block whenever it rears its big ugly head. I have also designed a printable flier for you to put up in your writing area, so you can always have these tips equipped and at the ready when writer’s block strikes.

Writing everyday: If you are a writer, make writing a priority. The choice is up to you. If you’ve decided writing is your purpose, then make it a daily practice and make no exceptions. Tell yourself the affirmation: Writers write. I am a writer, and I am going to write. Set aside a specific time each day that you sit down and write. You will likely need more time to research, brainstorm, read, and do other writing-adjacent activities, but make sure you write every.single.day. Start with five, ten, fifteen, or thirty minutes at a time, depending on your experience and ability. If you haven’t written in months or years, set aside five minutes each day to write. Find some writing prompts or writing exercises and set a timer, then write until the timer beeps. Chances are you will feel compelled to continue writing past the time you set, but don’t force yourself to do so. If you want to spend five minutes each day working on the same writing project, you can do that too. Gradually increase your writing time as you strengthen those writing muscles and build the habit into your life. It takes twenty-one days to build a habit. That comes out to 1.75 hours across three weeks. When broken down into manageable chunks, a consistent, daily writing practice becomes more possible and over time, it becomes less like a manual task and more automatic. Five minutes every day. That’s all it takes!

Writing workspace: To make your daily writing practice easier, design a workspace that makes you want to write. Invest in a comfortable desk chair or a standing desk if necessary. Turn on soft lighting and play some instrumental music to help relax your mind while you let the creative juices flow. Make sure you have snacks and a nice warm beverage on hand. You can train your brain to get into writing mode by doing the same thing at the same time every day and employing all five senses to reinforce the habit. For example, if you want to write for ten minutes every day, starting at 7:00 p.m., start by playing your favorite song or an instrumental track you enjoy to remind yourself that it's time to write. Bonus points if you set an alarm to go off at 7:00 p.m. with the song, so it's automated and not on you to remember. While the song is playing, make yourself a cup of tea, grab a fruit or bag of chips, and get your workstation and timer ready. When you’re ready to go, start writing, and don’t stop. Remember, you’re not writing the most amazing, perfect words ever put together on earth. Just write.

Establish a rewards system that incentivizes you to write. We all enjoy different things—some of us enjoy shopping, others enjoy playing video games, and some enjoy eating delicious food. Without being counterproductive to your other goals or negatively impacting your health, come up with a rewards system that will help you reach your writing goals. If it’s your goal to write so many words each week, set a reward that will encourage and excite you to sit down to write and accomplish that goal. For example, I would like to buy a new book or two. I won’t get a new book until I finish reading one I already own, so I don’t have a bunch of unread books on my shelf. The same principle goes for writing. If you want to reach that weekly word count goal, write for the reward. You don’t have to write perfectly, just get those words onto the page.

Take care of yourself and your health: This advice is not just for writers, but because writing is so personal and tied to our mental and emotional health, self-care is an important step in creating a lifestyle that supports writing. Get plenty of quality sleep, practice good hygiene, maintain a healthy diet, and exercise regularly. For people with disabilities, mental illness, or neurodivergence, get any necessary assistance if you haven’t yet.

Some Additional Tips For Combatting Writer’s Bock

Try morning pages or a brain dump. Before you sit down to write or work on an ongoing project, try freeing your mind. The concept of “Morning Pages” comes from Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, and can be an effective strategy for getting all the mental distractions out of your way before you actually start writing. Like the name suggests, brain dump pages or morning pages are simply a page or two of everything on your mind that you want to offload so you can think clearly. It can be total nonsense, a to-do list, a stream of consciousness, a series of mad ramblings —whatever it is, get it out of your head and onto the page so you can make room for the real writing.

Let yourself write garbage. If you’re struggling with perfectionism and overcoming your judgmental internal editor, let yourself be okay with writing garbage. Create a new draft and title it “trash draft” if you like. Then write with reckless abandon. You can write about whatever you like or you can work on a project you’ve been writing. Make your internal editor take a backseat to your internal writer and watch as the story takes shape on the page. No writer creates perfection in the first draft, so stop telling yourself the rough draft is bad. A garbage page is better than nothing. You can create treasures from a pile of trash, but you cannot edit a blank page.

Get involved in a writing community. If external accountability is more effective for you, get connected with other writers. Network with writers, editors, publishers, and published authors for advice, craft tips, editorial news, and external motivation to keep writing. Sometimes, having a writing community can be more powerful for combating writer’s block that a routine or paycheck. Writing communities are a great way for writers to celebrate one another’s accomplishments and receive truly helpful feedback on writing.

Writer’s Block As A Result of Burnout

If you’ve made it this far, then the next piece of advice will sound quite contradictory to everything said thus far. If you’re experiencing writer’s block as a symptom of burnout, take a break. Stop writing. I know, it sounds crazy! First, I’m telling you to write, then telling you not to write. Trust me.

If you’ve done everything advised so far and nothing has worked, don’t force yourself to write when you just can’t. I’m not saying give up, but give yourself time and patience to recover from the burnout before jumping back into writing. When it is time to dive back in, do so slowly and with grace. Stick your toe in the water before diving in headfirst. If you’ve been stuck on a book for years and nothing you do can make you want to continue writing it, try writing something else. Take a break. When it’s time, you’ll come back to it. And if it’s time for you to pivot, don’t judge yourself for doing so. It may be time for a change.

Thinking Realistically About Creativity

Creativity sometimes comes from a spark of inspiration, the elusive mystical muse that chooses to strike at random. But most often, creativity is a skill you practice regularly, and it’s not as glamorous as the media makes it seem. Writing is hard work and it requires a healthy lifestyle, commitment, vulnerability, and consistency rather than artistic brilliance. Either you’ve chosen to be a writer, or writing has chosen you. If this is indeed the path you wish to take, you must go all in. I’m not telling you it’s always easy, but it does get easier with time, practice, and perseverance. When I first started out, I went years between working on chapters of the same book. Now, I write multiple blog posts each week. I still struggle with feeling motivated or excited to write. Whenever I’m dragging myself to my writing desk rather than running, go through the steps to ensure I am doing everything in my power to get myself to write. It usually works, and then once in a while it doesn’t and I know it’s time for a break. Give yourself some grace as a writer and as a human. There's a million things out there that could affect you or get in the way of your writing practice. But if you’re dedicated, determined, and willing to put in the effort, you can be a writer, and your writing will improve with every session.

You’re a writer. Writing is what you do. It’s in your bones. It is your purpose and your reason. Writing is your destiny. Now write.

Thank you for taking the time to read this blog post. I hope it helped you to better understand yourself as a writer, the struggle of writer’s block, and how to overcome it and become a better writer. If you enjoyed this post or if it helped you in some way, please leave me a comment! I’d love to know your thoughts! If you’d like to read more writing advice from me, please check out the recent posts from my blog below!

Bibliography

Hayes, Payton. “How To Overcome Writer’s Block.” Shayla Raquel’s Blog, February 7, 2023.

Hayes, Payton. “Diagnosing & Treating Writer’s Block.” Graphic created with Canva, February 7, 2023.

Hayes, Payton. “How To Defeat Writer’s Block.” Graphic created with Canva, February 7, 2023.

Related Topics

Know The Rules So Well That You Can Break The Rules Effectively

Writing Every Day: What Writing As A Journalist Taught Me About Deadlines & Discipline

7 Amateur Writer Worries That Keep You From Taking The Plunge (And Ultimately Don't Matter)

Yoga For Writers: A 30-Minute Routine To Do Between Writing Sessions

For Content Creators and CEOs with ADHD: Strategies to Succeed Despite Overwhelm and Distractions

8 Ways To Level Up Your Workspace And Elevate Your Productivity

How To Organize Your Digital Life: 5 Tips For Staying Organized as a Writer or Freelancer

Recent Blog Posts

*This article was originally posted in 2023 as an online exclusive for Shaylaraquel.com, but since the site is currently offline, I’ve reposted my article here so other writers can try the tips and tricks that worked for me. If Shaylaraquel.com goes live again, I will redirect traffic back to the original post.

Written by Payton Hayes. | Last Updated: March 17, 2025.How To Write Poems With Artificial Intelligence (Using Google's Verse by Verse)

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been integrated into various creative fields, including poetry. Google's experimental tool, Verse by Verse, assists users in composing poems by offering suggestions inspired by classic American poets. To use the tool, individuals select up to three poets from a list that includes Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and Edgar Allan Poe. After choosing the desired poetic structure—such as quatrain, couplet, or free verse—and specifying parameters such as syllable count and rhyme scheme, users input the first line of their poem. The AI then generates subsequent lines, emulating the style of the selected poets. It's important to note that while AI can provide creative suggestions, human intervention remains crucial in refining and finalizing the poem, ensuring authenticity and personal expression.

Hi readers and writerly friends!

If you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by, and if you’re a returning reader, it’s nice to see you again! In this post we’re going to explore writing poetry using artificial intelligence (AI). I heard about this from an article a few years ago. I tried to find it, but so many others have come out discussing the same topic since then and it seems it’s been buried in the search results. However, I have linked some particularly interesting articles at the end of this post for further reading. All other articles quoted in this post will be linked at the end as well.

*Please note that exclusively using AI to write and publish text-based content is unethical and should not be done under any circumstance. In this post, I demonstrate how to utilize AI as a tool for writing practice, but I do not condone the use of AI to produce text without extensive editing and human intervention. In fact, I highly advise against it. In absolutely no cases should AI-written content be submitted to editors, agents, or publishers, nor should it be published online or in print materials. AI should never be used to replace the art of writing and storytelling through text. This is just a fun, light-hearted post that shows how writers can experiment with AI to help get their creativity flowing, much like warming up with writing exercises. Please keep in mind that AI use poses various ethical and environmental ramifications. I strongly encourage you to do your own research before trying out the techniques in this blog post for yourself.

Artificial Intelligence

Before we can create poetry using artificial intelligence, we must first understand what the term means in definition as well as what it means for the future of humanity. Artificial intelligence is changing the world in ways no one can yet fully predict.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) of Oxford University Press defines artificial intelligence as:

“Noun. The capacity of computers or other machines to exhibit or simulate intelligent behaviour; the field of study concerned with this. Abbreviated AI.” (OED 2008)

Artificial intelligence can also be described as the theory and development of computer systems that are able to perform tasks such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, translation between languages, and other tasks that normally require human intelligence. Initially, AI included search engines, recommendation algorithms such as those used by YouTube, Amazon, and Netflix, computer programs that could play games like chess with users. In the last decade, we have seen an emergence of AI applications that can complete a myriad of tasks that typically require human intelligence. These applications include understanding and responding to human speech (apps such as Siri and Alexa), self-driving cars (such as Tesla), and even art making and poetry writing programs (such as the infamous Lensa app and Verse by Verse by Google).

In his article, “Can AI Write Authentic Poetry?” cognitive psychologist and poet Keith Holyoak explores whether artificial intelligence could ever achieve poetic authenticity. In the article, he makes the comparison of AI to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein:

“On the hazier side of the present horizon, there may come a tipping point at which AI surpasses the general intelligence of humans. (In various specific domains, notably mathematical calculation, the intersection point was passed decades ago.) Many people anticipate this technological moment, dubbed the Singularity, as a kind of Second Coming—though whether of a savior or of Yeats’s rough beast is less clear. Perhaps by constructing an artificial human, computer scientists will finally realize Mary Shelley’s vision.” (Holyoak 2022, par.6)

Despite the bleak predictions of how AI may one day replace all human activity, the reality is that this technology is simply not there yet. While AI can simulate human intelligence successfully in many tasks, it is still lacking in the poetry writing department and requires humans to be the editors and final decision makers in the outcome of a poem. Holyoak explains this current iteration of poetry AI being a system that “operates using a generate-then-select method” (Holyoak 2022, par.10).

In his article, Keith Holyoak ponders the validity of AI poetry, functionalism, the Hard Problem of consciousness, and the critical essence or subjective experience within poetry. I have linked his article at the end of this blog post, and I highly encourage you to read it if you’re even remotely interested in these topics.

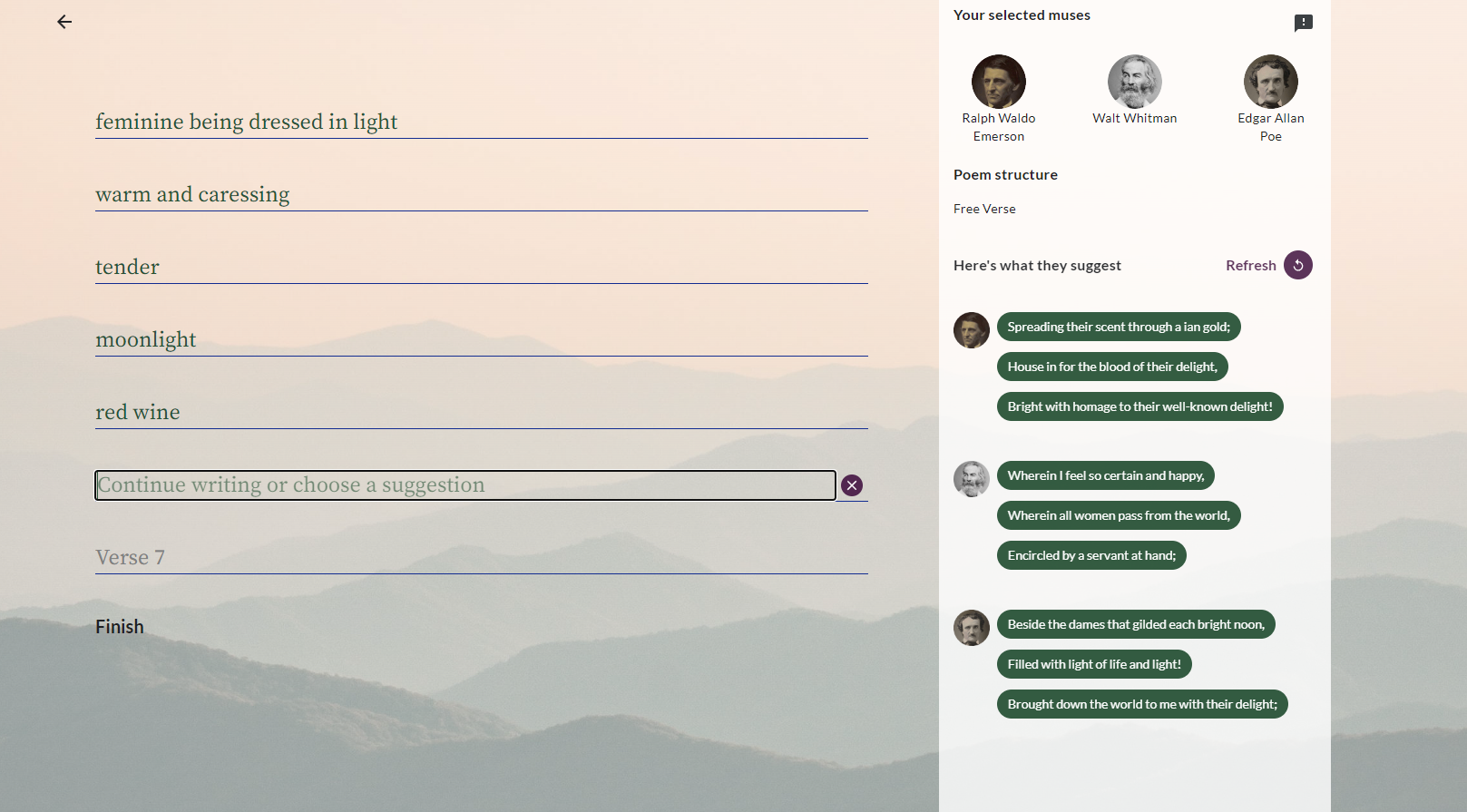

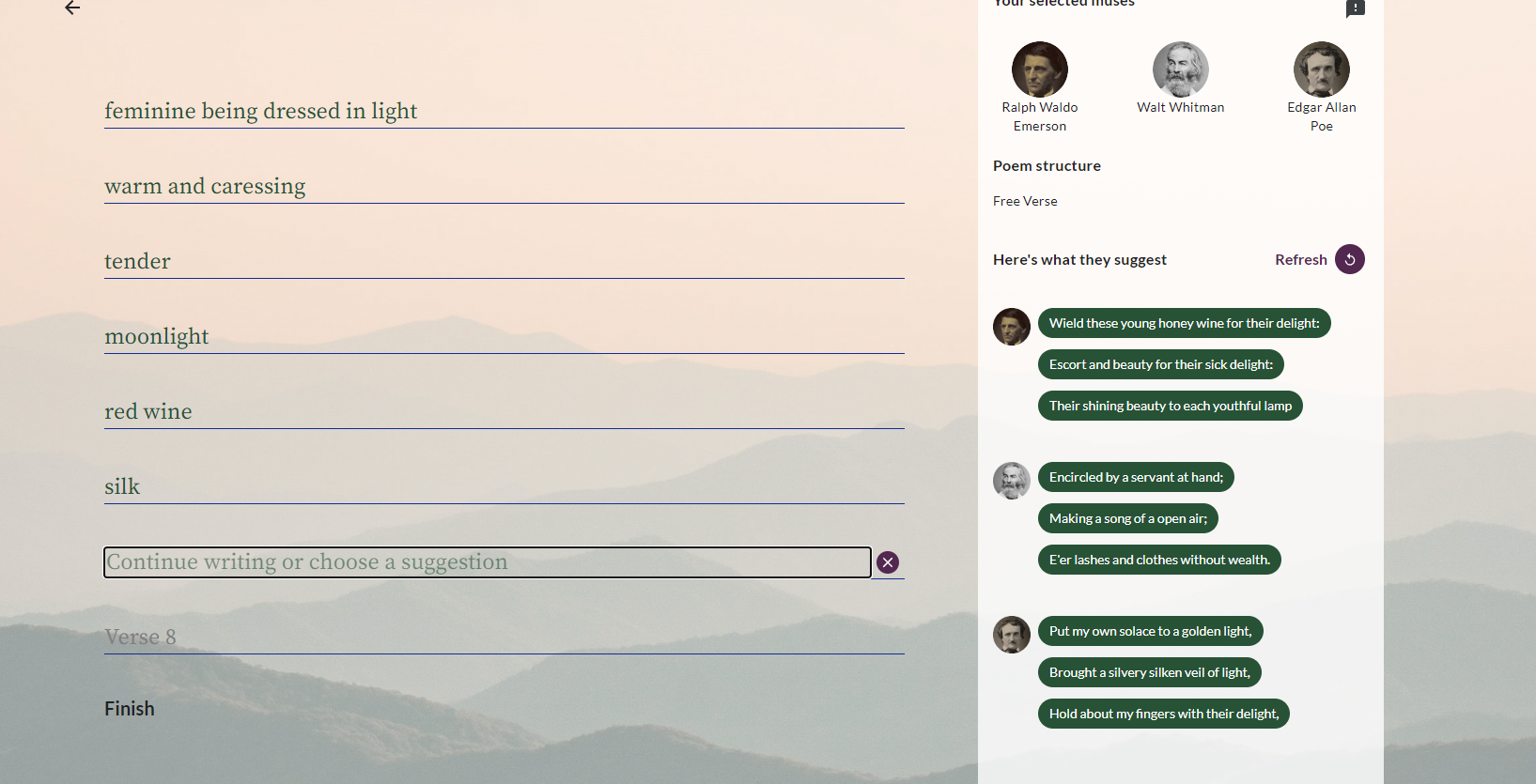

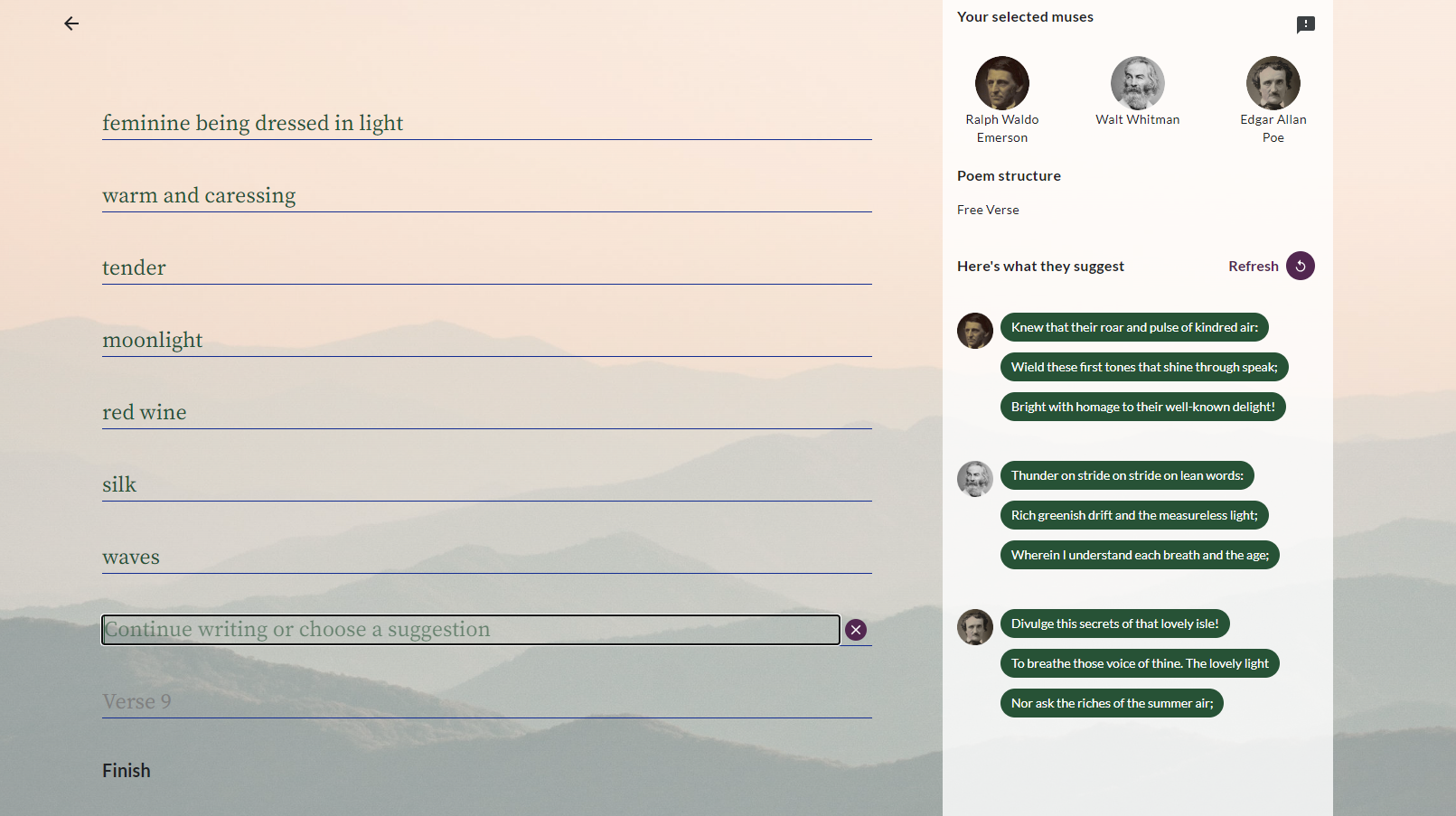

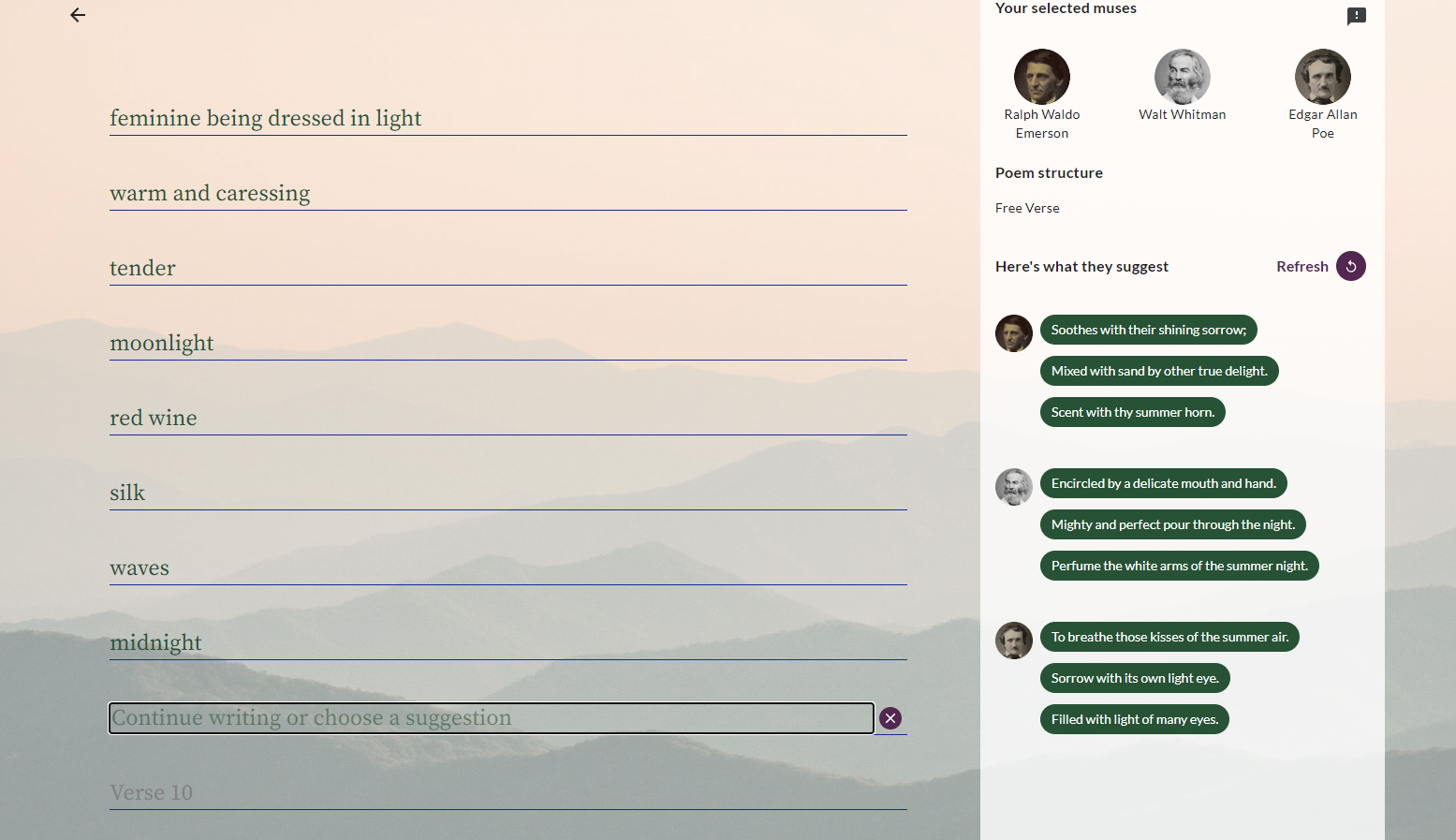

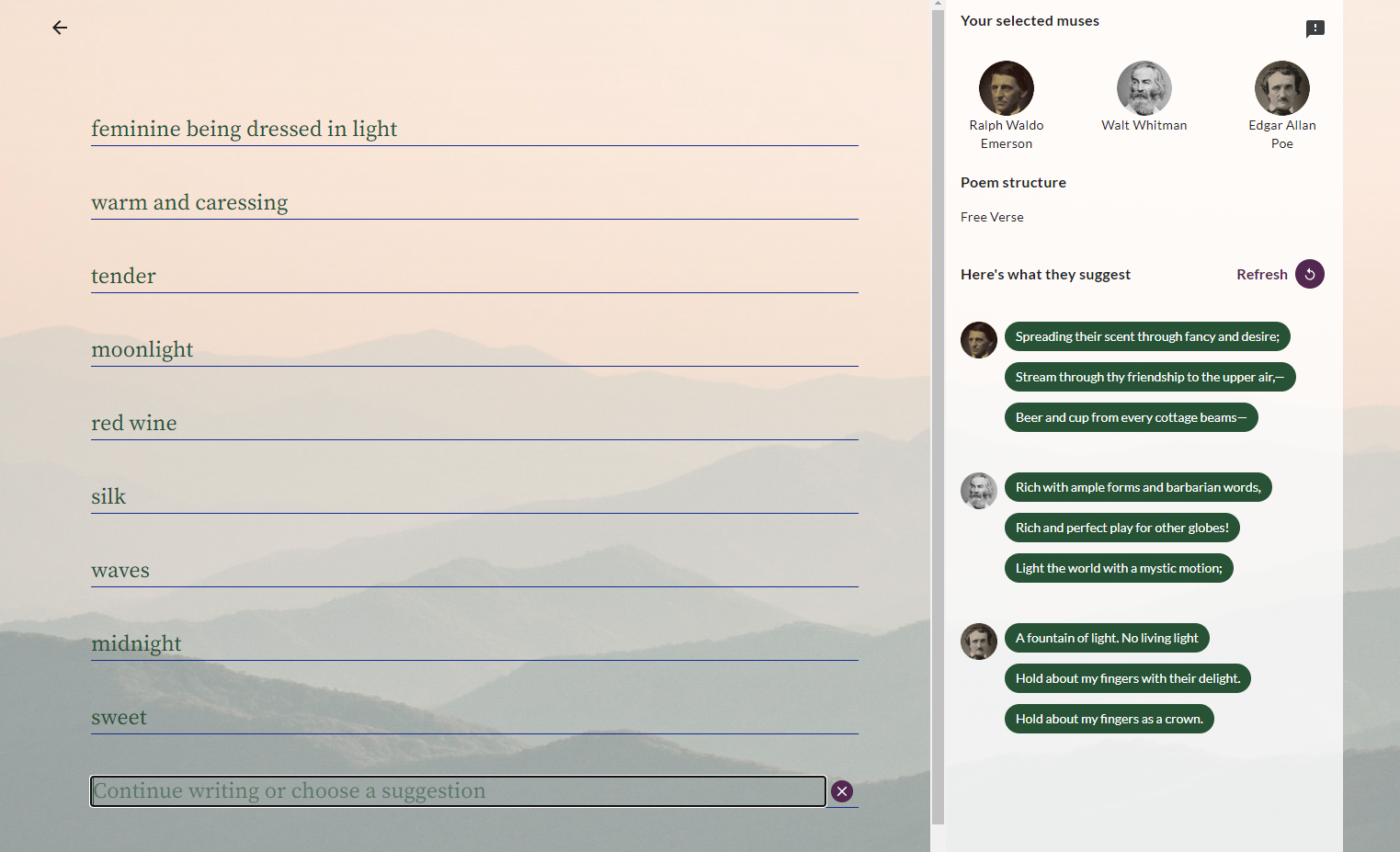

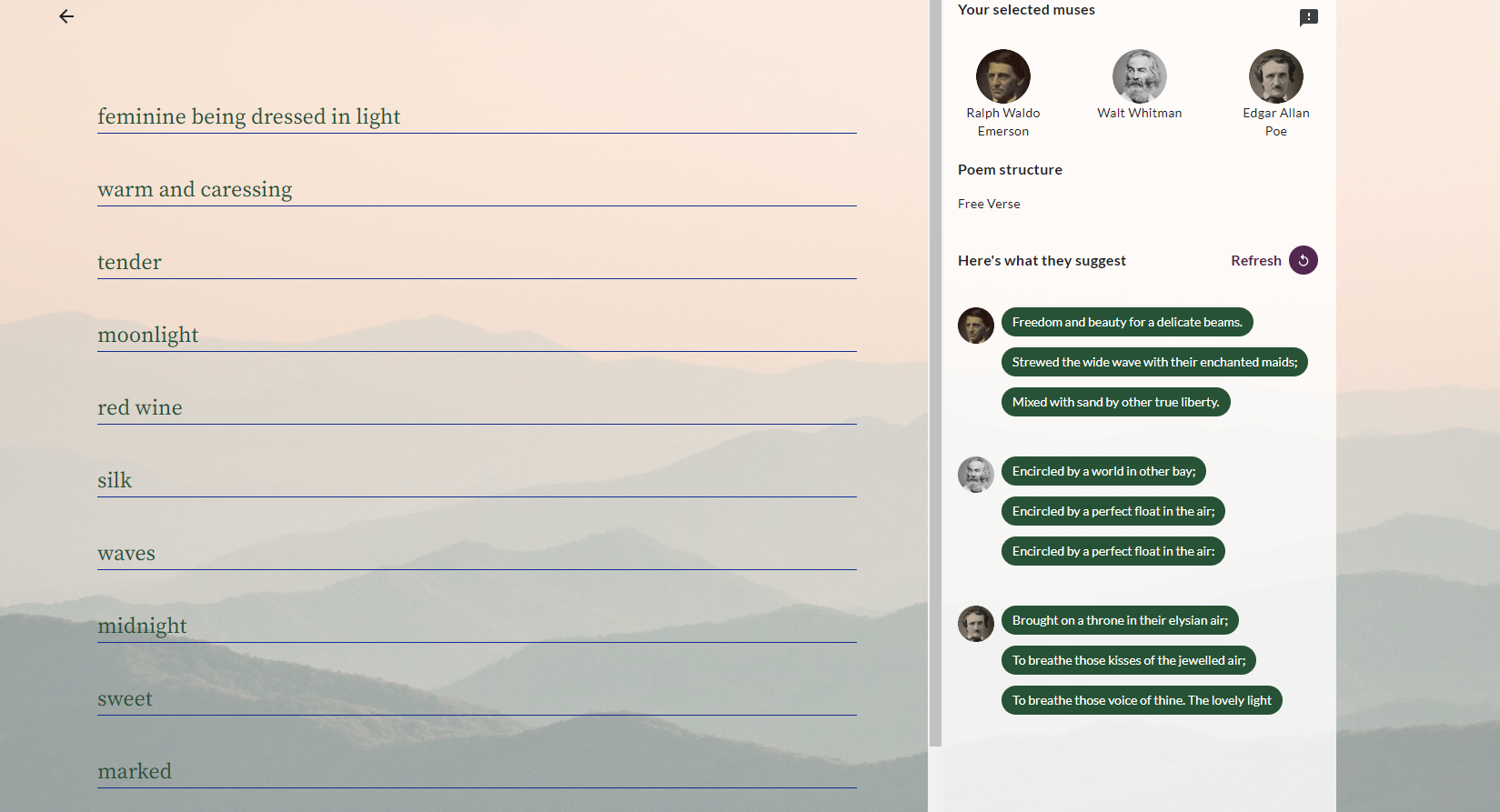

Users can select up to three poets to serve as their muses. They will provide suggestions as you write. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Google’s Verse by Verse

Verse by Verse is a powerful poetry-writing AI created by Google that produces suggestions line by line, inspired by famed classical poets such as Emily Dickinson, Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. The tool allows users to select up to three poets they want to mimic from a list of twenty-two classical poets.

Google’s about section on the Verse by Verse demo page says this of the software:

“Verse by Verse is an experiment in human-AI collaboration for writing poetry. We have created a cadre of AI poets, trained on the poems of many of America's classical poets, to work alongside you in writing poetry.

Each poet will try to offer suggestions that they think would best continue a poem in the style of that given poet. As such, try working with different poets to see whose style best meshes with your own.

Explore what works best for you when composing the poem. You can try using the poets' suggestions (including editing them to better match your style!), or write your own inspired by what they suggest.” (Google)

I conducted a little more research to gain a better understanding of how the AI operates and how best to use it for writing my own poetry. The article “Google’s ‘Verse by Verse’ can help you write poetry” by Aditya Saroha provides insight into how the muses provides suggestions based on classical poets. Saroha said, “Google explained that Verse by Verse's suggestions are not the original lines of verse the poets had written, but novel verses generated to sound like lines of verse the poets could have written. To build the tool, Google’s engineers trained models on a large collection of classic poetry. They fine-tuned the models on each individual poet’s body of work to try to capture their style of writing” (Saroha 2021, par.8-10). So, the poetry that the tool’s muses provide the user with were not actually lines crafted by classical poets, but rather inspired by their individual bodies of work.

In the article, “Google’s ‘Verse by Verse’ Lets You Imitate Writing Style Of Your Favourite Classical Poet” by Rudrani Gupta, provided quotes from one of Google’s software engineers, Dave Uthus where he explained how the AI was trained to write like classical poets. She said, “The suggestions of the new verses are possible because the tool has been ‘trained to have a general semantic understanding of what lines of the verse would best follow a previous line of verse,’ said engineer Dave Uthus. ‘Even if you write on topics not commonly seen in classic poetry, the system will try its best to make suggestions that are relevant,’ he added” (Gupta 2020, par.4). By training the AI in this fashion, the tool allows modern poets to write about modern topics, themes, and concepts, while imitating classical style and voice.

While this software can prove to be a useful writing too, it isn’t intended to replace talented poets. Saroha concludes his article by noting that the tool is meant to aid poets rather than replacing them. He said, “Through the tool, Google aims to ‘augment’ the creative process of composing a poem. Google said Verse by Verse is a creative helper, an inspiration and not a replacement” (Saroha 2021, par.11 ).

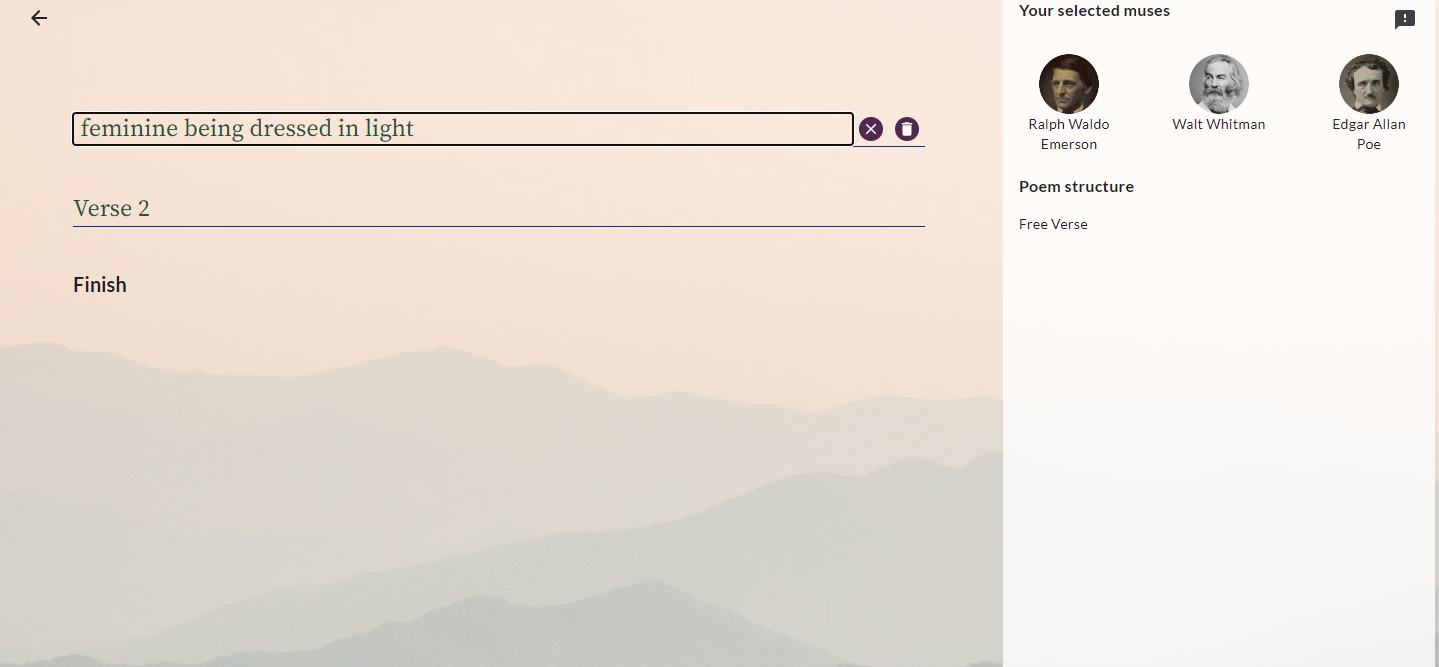

Google’s Verse by Verse, an AI poetry-writing tool. Photo by Payton Hayes.

I First Used Verse by Verse In 2020

I was first introduced to Verse by Verse in 2020 and I tried it just to see how effective it could be. At the time, I was really getting into my own religious deconstruction and exploring overt sexuality and expression. As a result, my writing at the time certainly reflected my interests and spiritual journey. I typed in words such as holy, prayer, pleasure, love, lust, sex, worship, devotion, god, and church. The poets I selected as my muses were Whitman, Emerson, and Poe and as I wrote each verse on the left, they provided me with inspiration from the column on the right.

I do not have the original poem the AI created when I first did this exercise in 2020 however, from that, I ended up with the following poem:

PRAYER

"Oh God," she says, hands clasped together, fingers entwined, knees bent.

He doesn't answer; he does.

he answers with earnest, continued, devoted worship

head bowed, eyes closed, his mind devoid of all else but this

—this soul-shaking, earth-shattering pleasure, this blessed communion between man and woman,

the Holy Spirit an undoubted voyeur through the candlelight,

this holy practice wherein they do some of their finest praying. (Hayes 2020)

Revisiting Verse by Verse in 2022

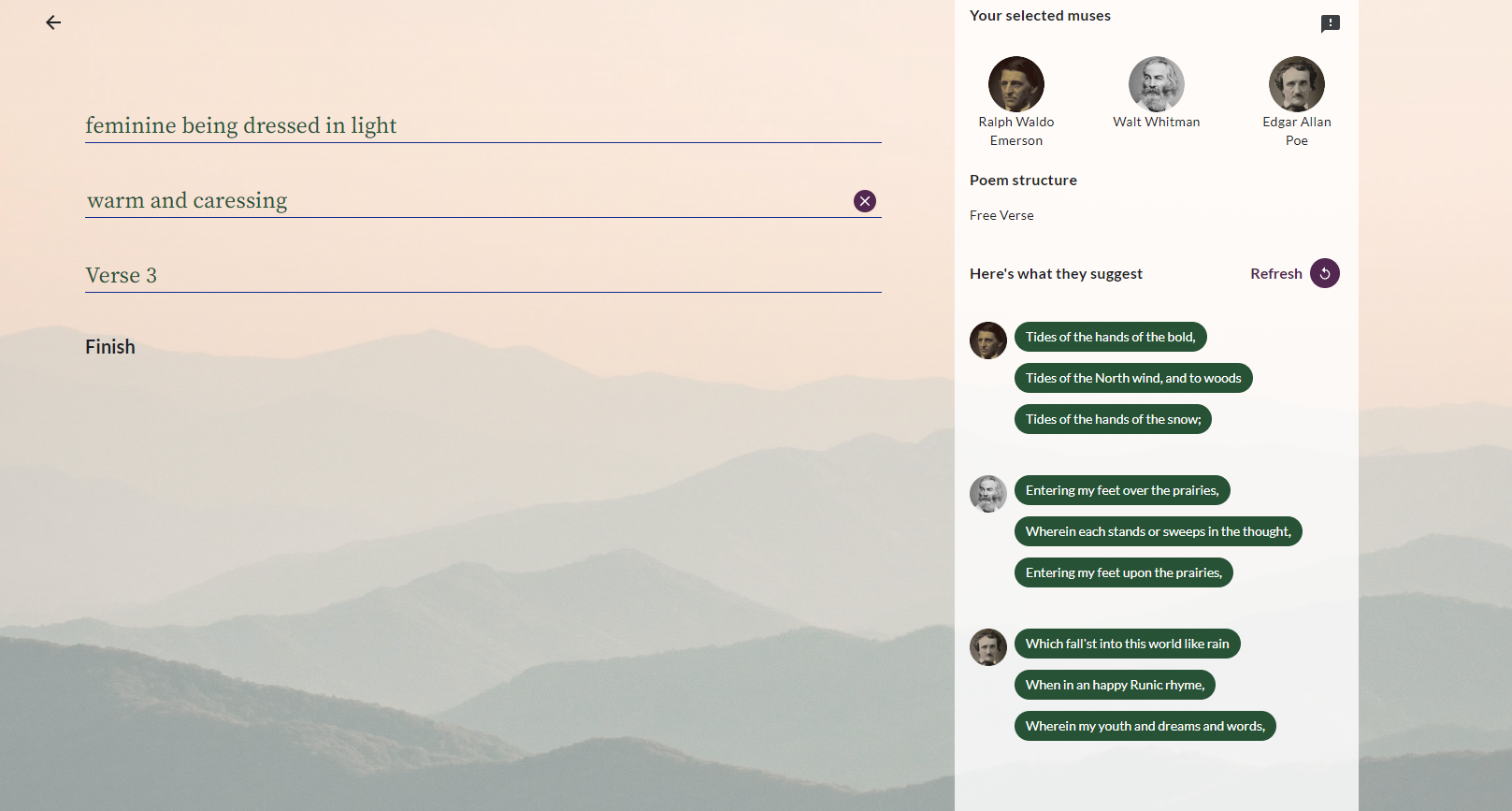

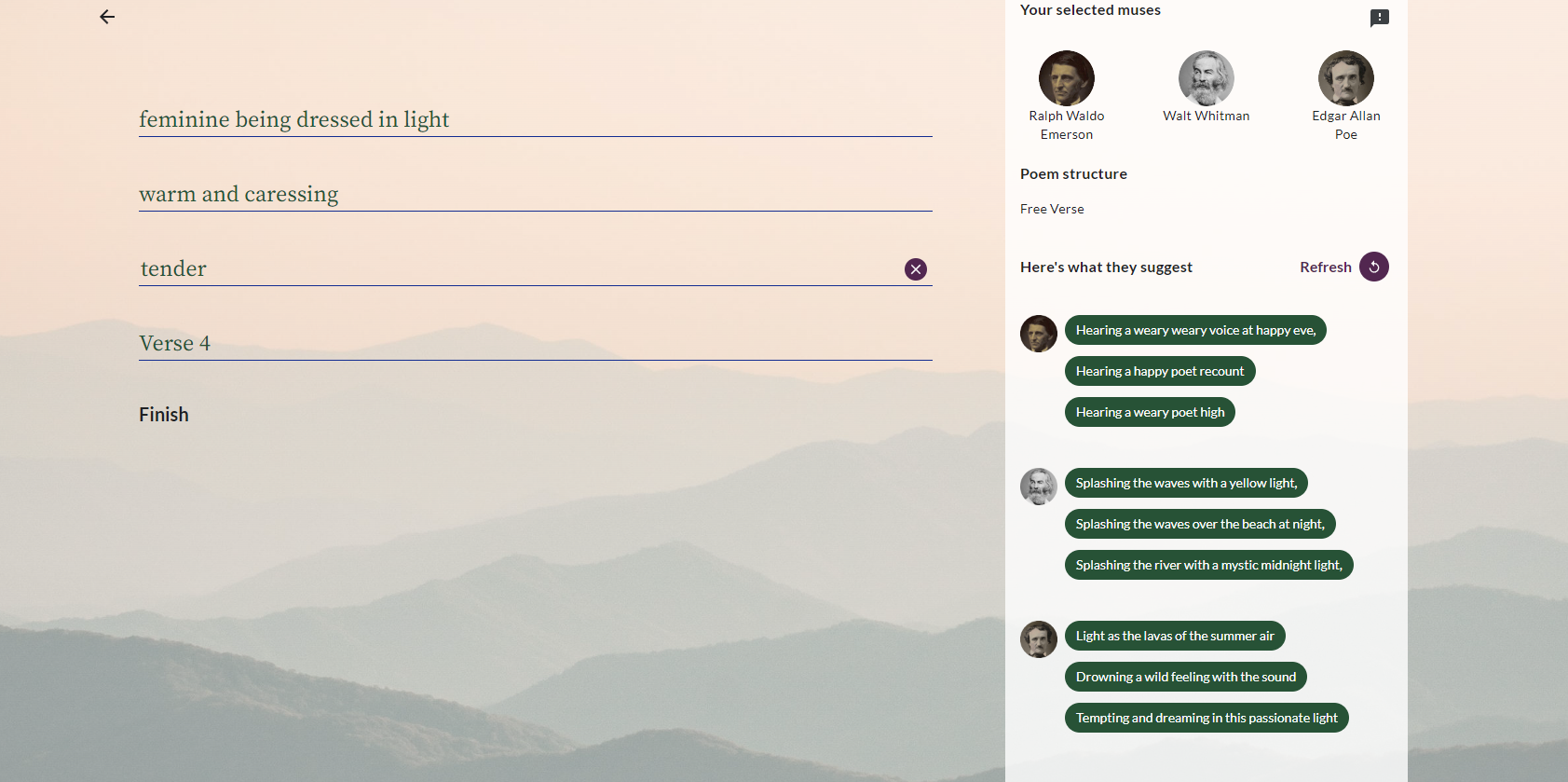

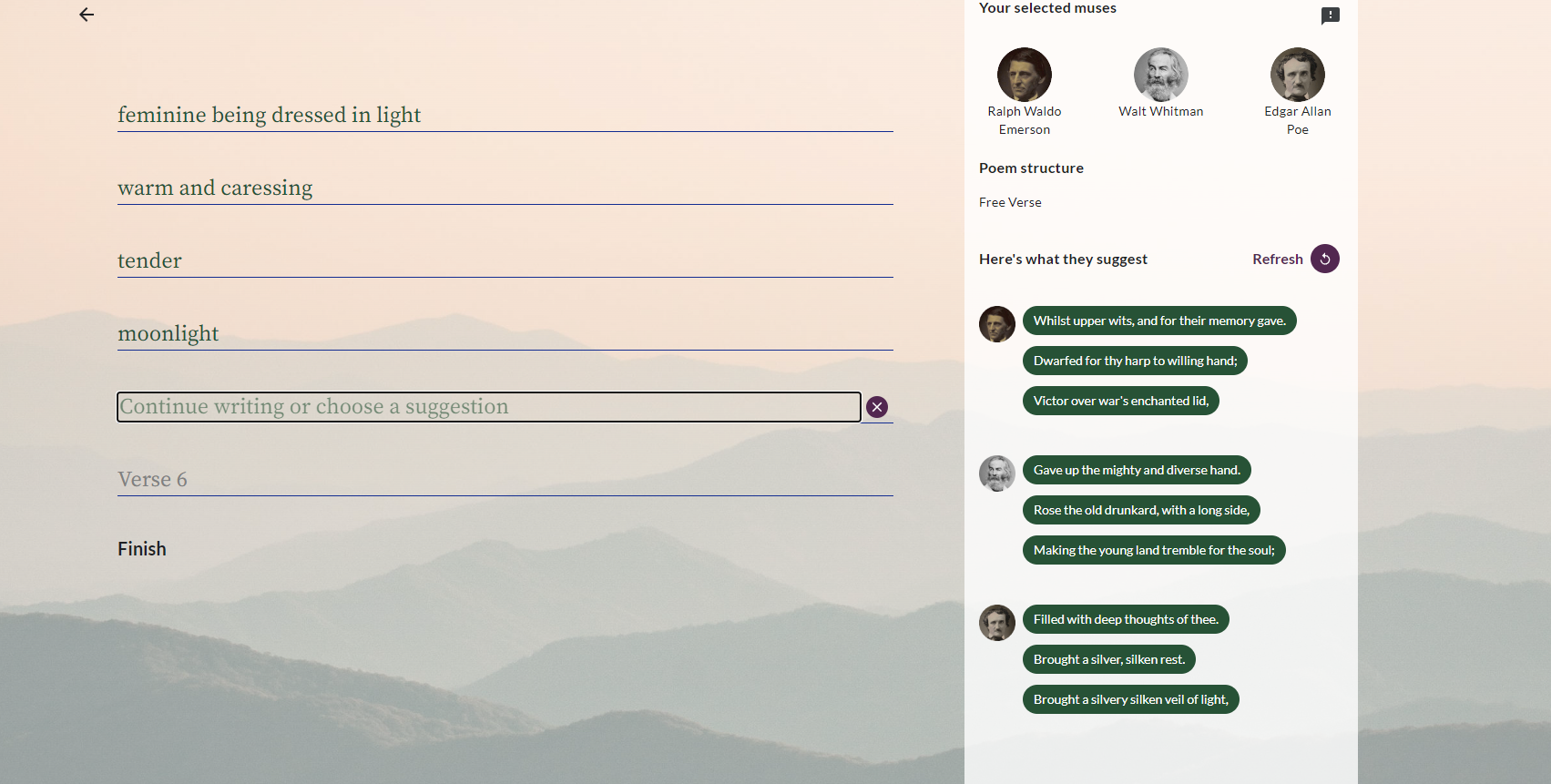

To show you how this AI writes poetry and how it’s suggestions can be effective for your own poetry writing, I decided to give it another go in 2022. Below is a gallery of screenshots from the tool as I entered each verse/line at a time. As you can see, my muses Emerson, Poe, and Whitman all provided me with interesting and unique suggestions to include in my poem.

I used words and phrases that came to mind, without rhyme or reason. I typed out ten verses and my chosen muses produced three lines each to help inspire my poem. Below are the twenty-seven lines from each poet in the right column (totaling eighty-one lines among my muses).

Ralph Waldo Emerson Muse

Tides of the hands of the bold,

Tides of the North wind, and to woods

Tides of the hands of the snow;

Hearing a weary weary voice at happy eve,

Hearing a happy poet recount

Hearing a weary poet high

Whilst upper wits, and for their memory ave

Dwarfed for thy harp to willing hand;

Victor over war’s enchanted lid

Spreading their scent through a ian gold;

House in for the blood of their delight,

Bright with homage to their well-known delight!

Wield these young honey wine for their delight:

Escort and beauty for their sick delight:

Their shining beauty to each youthful lamp

Knew that their roar and pulse of kindred air:

Wield these first tones that shine through speak;

Bright with homage to their well-known delight!

Soothes with their shining sorrow;

Mixed with sand by other true delight.

Scent with thy summer horn.

Spreading their scent through fancy and desire;

Stream through thy friendship to the upper air,--

Beer and cup from every cottage beams–

Freedom and beauty for a delicate beams.

Strewed the wide wave with their enchanted maids;

Mixed with sand by other true liberty.

Walt Whitman Muse

Entering my feet over the prairies,

Wherein each stands or sweeps in the though,

Entering my feet upon the prairies

Splashing the waves with a yellow light,

Splashing the waves over the beach at night,

Splashing the river with a mystic midnight light,

Gave up the mighty and diverse hand

Rose the old drunkard, with a long side,

Making the young land tremble for the soul;

Wherein I feel so certain and happy,

Wherein all women pass from the world,

Encircled by a servant at hand;

Encircled by a servant at hand;

Making a song of a open air;

E’er lashes and clothes without wealth.

Thunder on stride on stride on lean words:

Rich greenish drift and the measureless light;

Wherein I understand each breath and the age;

Encircled by a delicate mouth and hand.

Mighty and perfect pour through the night.

Perfume the white arms of the summer night

Rich with ample forms and barbarian words,

Rich and perfect play for other globes!

Light the world with a mystic motion;

Encircled by a world in other bay;

Encircled by a perfect float in the air;

Encircled by a perfect float in the air:

Edgar Allan Poe Muse

Which fall’st into this world like rain

When in an happy Runic rhyme,

Wherein my youth and dreams and words,

Light as the lavas of summer air

Drowning a wild feeling with the sound

Tempting and dreaming in this passionate light

Filled with deep thoughts of thee.

Brought a silver, silken rest.

Brought a silver silken veil of light,

Beside the dames that gilded each bright noon,

Filled with light of life and light!

Brought down the world to me with their delight;

Put my own solace to a golden light,

Brought a silvery silken veil of light,

Hold about my fingers with their delight,

Divulge this secrets of that lovely isle!

To breathe those voice of thine. The lovely light

Nor ask the riches of the summer air;

To breathe those kisses of the summer air.

Sorrow with its own light eye.

Filled with light of many eyes.

A fountain of light. No living light

Hold about my fingers with their delight

Hold about my fingers as a crown.

Brought on a throne in their elysian air;

To breathe those kisses of the jewelled air;

To breathe those voice of thine.The lovely light

So, the muses definitely wrote…something. It’s not necessarily poetry —yet.

From those lines, I narrowed them down to my favorites in the following lines:

Wield these young honey wine for their delight:

Their shining beauty to each youthful lamp

Splashing the river with a mystic midnight light,

Wherein I feel so certain and happy,

Encircled by a delicate mouth and hand.

Light the world with a mystic motion;

Tempting and dreaming in this passionate light

Brought a silver silken veil of light,

Put my own solace to a golden light,

Brought a silvery silken veil of light,

Hold about my fingers with their delight,

To breathe those kisses of the summer air.

Here, you could put these lines back into the AI to see what you get. I decided to rework them myself to make them less abstract. The lines crossed out above, I ended up using below. I kept my first verse, “feminine beauty dressed in light” and used that as the first line for the poem.

Feminine being dressed in light

To breathe those kisses of the summer air

Held about her fingers my delight

Washed softly away my every care

Encircled by a delicate mouth and hand

Wherein I feel so happy and certain

Her shining beauty imprinted in the sand

She is most deserving of devotion

You don’t have to use all of the lines the muses provided you with. As you can see, I have only used a handful here. This poem isn’t complete, but you get the idea. I’m going to set these lines aside for use with another poem later. The suggestions from the muses in the tool may not have been completely sensible or eloquent, but its a great starting point for poets who may be stuck. It’s also a great way to practice mimicking your favorite classical poet’s writing style if you’d like. Although AI cannot yet write poetry that is indistinguishable from human poetry, it can certainly serve as a useful tool in your own poetry practice.

The next time you find yourself stuck on a line, try using AI to help you finish out your poem! If you try this, leave your work in the comments below! What was your favorite line the muses came up with? Let me know below!

Thank you for reading this blog post and if you’re interested in reading more about AI poetry or delving deeper into the sources I mentioned above, check out the bibliography and further reading sections below! Additionally, if you’d like to read similar posts, check out the related topics section. Lastly, if you want to read more posts from me, check out my recent blog posts.

Bibliography

Saroha, Aditya. “Google’s ‘Verse by Verse’ can help you write poetry.” The Hindu, November, 28, 2021. (Paragraphs 8 and 10-11).

Google, “Verse By Verse” Google AI: Semantic Experiences. (AI Writing Tool and About Section).

Hayes, Payton. “Google’s Verse by Verse.” Photos, January, 16, 2023 (Photo Gallery).

Further Reading

“Google’s New AI Helps You Write Poetry Like Poe.” by Matthew Hart, November 24, 2020.

“Can AI Write Poetry? — Look at the Examples to Decide.” by Kirsty Kendall, May 4, 2022.

“Why Tomorrow’s Poets Will Use Artificial Intelligence.” by Lance Cummings, July 1, 2022.

“What Happens When Machines Learn To Write Poetry.” by Dan Rockmore, January 7, 2020.

Related Topics

Writing Exercises from Jeff Tweedy's Book, How To Write One Song

Experimentation Is Essential For Creators’ Growth (In Both Art and Writing)

Screenwriting for Novelists: How Different Mediums Can Improve Your Writing

“Twenty Little Poetry Projects” Writing Exercise by Jim Simmerman

How To Write Poems With Artificial Intelligence (Using Google's Verse by Verse)

Why Fanfiction is Great Writing Practice and How It Can Teach Writers to Write Well

Writing Every Day: What Writing As A Journalist Taught Me About Deadlines & Discipline

Recent Blog Posts

Written by Payton Hayes | Last Updated: March 18, 2025“Twenty Little Poetry Projects” Writing Exercise by Jim Simmerman

The "Twenty Little Poetry Projects" is a creative writing exercise devised by Jim Simmerman, featured in The Practice of Poetry by Robin Behn and Chase Twichell. This exercise presents poets with twenty prompts designed to invigorate their writing process and explore unconventional poetic techniques. By engaging with these varied prompts, poets can break free from conventional patterns, experiment with new forms, and infuse their work with fresh perspectives. This exercise encourages the blending of sensory experiences, the use of unexpected language, and the creation of imaginative scenarios, all contributing to the development of a more dynamic and original poetic voice.

A photo of the book The Practice of Poetry: Writing Exercises From Poets Who Teach, by Robin Behn and Chase Twichell on a wooden coffee table. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Hello readers and writerly friends!

If you’re a returning reader, welcome back and if you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by! In this blog post I’ll be showing you how to write a poem from a bunch of seemingly nonsensical lines. “Twenty Little Poetry Projects” is a creative writing exercise created by Jim Simmerman, and published in The Practice of Poetry, by Robin Behn and Chase Twichell. I’ve used this writing exercise a handful of times in the past and in recent projects and its always a lot of fun for writing poetry, so I’ll be showing you how to do it too! If you want to support the original sources of this exercise, consider picking up a copy of The Practice of Poetry, by Robin Behn and Chase Twichell from your favorite bookstore or checking out a copy from your local library (or through the amazing library apps at the end of this post)!

“Twenty Little Poetry Projects” by Jim Simmerman

Begin the poem with a metaphor.

Say something specific but utterly preposterous.

Use at least one image for each of the five senses, either in succession or scattered randomly throughout the poem.

Use one example of synesthesia [mixing the senses].

Use the proper name of a person and the proper name of a place.

Contradict something you said earlier in the poem.

Change direction or digress from the last thing you said.

Use a word [slang?] you’ve never seen in a poem.

Use an example of false cause-effect logic.

Use a piece of talk you’ve heard [preferably in dialect and/or which you don’t understand].

Create a metaphor using the following construction: The [adjective] [concrete noun] of [abstract noun]…

Use an image in such a way as to reverse its usual associative qualities.

Make the character in the poem do something he/she could not do in real life.

Refer to yourself by nickname and in the third person.

Write in the future tense such that part of the poem sounds like a prediction.

Modify a noun with an unlikely adjective.

Make a declarative assertion that sounds convincing but that finally makes no sense.

Use a phrase from a language other than English.

Personify an object.

Close the poem with a vivid image that makes no statement, but that echoes an image from earlier in the poem. (Simmerman)

Margo Roby’s “A Thousand And One Nights”

I will use these steps when my brain is not behaving, when I have an idea and don’t know where to go with it. There are steps I ignore, but not many. Below is the final draft as published in Lunarosity, a now defunct ezine. I was going nuts while typing the drafts from my old notes. I kept wanting to fix things and get rid of verbs of being. I also had to decipher the original below my first revisions.

I am a concrete person with my writing. When I first tried this, I was sitting on our bed, in Jakarta, because that was my work space. I was feeling downhearted with life—I wrote the first line. I had a small Persian carpet next to me I was staring at while trying to figure out how to do this prompt—I wrote the next line…

1. I am a prisoner without walls

2. among the flowers of my Persian carpet vines/weeds are beginning to sproutOnce I had a focus, a direction, I found the exercise much easier to carry out. I don’t think I can write this exercise without knowing where I am going. It would be interesting to try, though. Randomness has merit. (Roby)

With a draft to go on, I stopped worrying about the steps. I listed nouns and verbs that fit with Persian carpets and Middle Eastern fairy tales, circled words I wanted to look up for other possible meanings, and started back through this draft, trimming, adding line breaks, making the story active rather than passive. I got rid of lines that I had in only because the exercise asked for them.

I will use these steps when my brain is not behaving, when I have an idea and don’t know where to go with it. There are steps I ignore, but not many. Below [right] is the final draft as published in Lunarosity, a now defunct ezine. (Roby)

Margo Roby’s First Draft (With Each Step)

1. Begin the poem with a metaphor.

I am a prisoner without walls

2. Say something specific but utterly preposterous.

among the flowers of my Persian carpet vines/weeds are beginning to sprout

3. Use at least one image for each of the five senses, either in succession or scattered randomly throughout the poem.

They twine and curl reaching for me pulling me down into the fields of silk and wool; as I slide through warp and weft I hear the rustle of thread grasses. My nostrils fill with the pungency of sheep and goats and I taste the dryness of dust.

4. Use one example of synesthesia [mixing the senses].

The dampness of a blue silk river runs through my ears.

5. Use the proper name of a person and the proper name of a place.

Nearby, Omar Khayyam sits writing under a date palm, the white minarets of Nineveh on the horizon.

6. Contradict something you said earlier in the poem.

If a carpet can have a horizon.

7. Change direction or digress from the last thing you said.

The hunt was on; turbaned caliphs on Arabian steeds, bows and arrows slung across their backs, chased a leopard peering forever across his shoulder.

8. Use a word [slang?] you’ve never seen in a poem.

Tally ho and an arrow is loosed never hitting its mark,

9. Use an example of false cause-effect logic.

suspended eternally in mid-air by silken threads.

10. Use a piece of talk you’ve heard [preferably in dialect and/or which you don’t understand].

A thousand throats can be slit by one man running.

11. Create a metaphor using the following construction: The [adjective] [concrete noun] of [abstract noun]…

The towering trees of thought stand in an expectancy of silence

12. Use an image in such a way as to reverse its usual associative qualities.

and I stand in the trap free of danger

13. Make the character in the poem do something he/she could not do in real life.

my arms sliding around the leopard’s golden ruff;

14. Refer to yourself by nickname and in the third person.

Ducky would have run

15. Write in the future tense such that part of the poem sounds like a prediction.

to be hunted forever through threads of colour,

16. Modify a noun with an unlikely adjective.

chased by frozen horses

17. Make a declarative assertion that sounds convincing but that finally makes no sense.

trapped by a web of patterns

18. Use a phrase from a language other than English.

another playmate in the Bokharan fields.

19. Personify an object.

The arrows hum through the staring trees

20. Close the poem with a vivid image that makes no statement, but that echoes an image from earlier in the poem

and I am trapped in a web of patterns.

A Thousand and One Nights by Margo Roby

Among the flowers of my Persian carpet

vines sprout curl twine me into fields of silk

and wool. Sliding through warp and weft,

I hear the rustle of thread grasses, and

my nostrils fill with the pungency of feral cats,

I taste the dryness of dust, and the dampness

of a blue silk river runs through my ears.

A blend and blur of color mark the horizon

spots of russet and black resolving into a hunt

undisturbed by my addition to the scene.

Arabian steeds damp dark with silken sweat,

silent as Attic shapes, prance and wheel

through date palms and trees of fiery-fruited

pomegranate. Turbaned caliphs, bows slung

across their backs, chase a leopard forever

peering over his shoulder. An arrow loosed never

hits its mark eternally suspended by woven

threads. Trees stand in an expectancy of silence

as I move within zig-zags of light and shadow.

My arms slide round the leopard’s golden

ruff and I am bound by threads of color

to be hunted forever through fields of silk and

wool, chased by frozen horses, another

player in the weaving fields of Bokhara. (Roby 2014)

My First Poem Written Using Jim Simmerman’s “Twenty Little Poetry Projects” In 2018

In 2018, my creative writing class did this writing exercise and below is my poem that resulted from it. I tried my hand at this exercise again in 2022, which you’ll see in the next example further on. I don’t have my earlier drafts of the poem from 2018, so I’ll show you my writing process line by line with my more recent poem from 2022, like Roby did with hers. This poem was published in Rose State College’s annual literary journal, Pegasus XXXVII, in 2018. It was inspired by Hush, Hush by Becca Fitzpatrick. If you’ve read the series, let me know if you catch all the references! (I have no idea who Caroline Janeway is, by the way. I cannot remember who or what this name is referring to but it’s definitely a reference to… something.)

A photo of page 61 of Pegasus XXXVII with the poem “Angel” by Payton Hayes. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Angel by Payton Hayes

You were an angel

but feathers fall like bowling balls

when the air is missing from the room,

from your lungs.

You gasped when I called you out, a

baffled sound, surprised more so, only by

the startling sensation of your wings being torn off.

Though, that warranted bloodcurdling screams,

and rightfully received them.

You had us all fooled with silken lies,

but Caroline Janeway saw you in the back of Al’s

Pool Hall in Roseville, Minnesota, back in 1994.

And last I checked, heaven wasn’t in the back of Al’s Pool Hall.

She said that you were glued to the lips of some chick in a miniskirt,

that you looked like you’d had one hell of a time.

That’s when I put it all together: you weren’t an angel, you never were.

You’ve always been good at bending the truth, though.

Here I was thinking that you’d fallen from heaven,

but really, I’d just fallen for you.

Solitary walks through silent city streets seem to clear the air for me.

You needed to become a part of my past, but how

do I fix the damage that’s been done?

You had a broken halo and I, a broken heart.

I never knew you could be so savage.

The glittering look of endearment in your eyes was

lust and nothing more. I saw so much more.

You, Cupid, loose an arrow; though it sticks I can

no more than despise you, now.

I pluck it from my side, warm, sticky blood

running down in streams.

Janie would have fainted at such a sight.

I’d stand frozen, watching it all unfold before me.

Your bloodied, pristine, feathers litter the ground.

There I stood, trapped by a web of lies.

Yet, la mia anima è libera, my soul is free.

I feel more weightless, now, than any feather ever could.

Though, I suspect that they feel freed from you as well.

You were never an angel but you fell from grace.

I hand you the arrow, dried blood covering the silver tip.

(Hayes 2018, 61)

Revisiting Jim Simmerman’s “Twenty Little Poetry Projects” Writing Exercise In 2022

As mentioned, I tried this writing exercise out again for the second time in 2022. Although both rounds of working with this writing exercise got my poetry published in local literary journals here in Oklahoma, I personally feel the second poem is significantly more personal, eloquent, and sophisticated compared to the first poem. The poem I wrote back in 2018 was most definitely a concept poem and based heavily off of my favorite book series (at the time) and this poem from 2022 is rooted in my authentic, lived experience.

My First Draft (With Steps)

1. Begin the poem with a metaphor.

My father is a rock. He is strong, stable, and enduring.

2. Say something specific but utterly preposterous.

My family stands trapped, smiling behind the glass.

3. Use at least one image for each of the five senses, either in succession or scattered randomly throughout the poem.

The jagged shards are sharp, threatening to cut me and the irony is not lost on me. Holding up the frame to my nose, it smells of old and the figures behind the cracks are quiet and stock-still.

4. Use one example of synesthesia [mixing the senses].

I could almost taste the film of dust around its edges.

5. Use the proper name of a person and the proper name of a place.

The Payton of San Antonio is not the Payton of Oklahoma City, though she takes their riverwalks with her.

6. Contradict something you said earlier in the poem.

My father is crumbling.

7. Change direction or digress from the last thing you said.

My mother is fluid like a river. Fluid, taking up the shape of any container she occupies

8. Use a word [slang?] you’ve never seen in a poem.

Some would call her flexible, others call her flakey.

9. Use an example of false cause-effect logic.

I’ve made it this far without a mother, I must be fine without her.

10. Use a piece of talk you’ve heard [preferably in dialect and/or which you don’t understand].

She was just ‘round the corner. Just ‘round the corner.

11. Create a metaphor using the following construction: The [adjective] [concrete noun] of [abstract noun]…

The fathomless abyss of my childhood trauma gapes before me.

12. Use an image in such a way as to reverse its usual associative qualities.

I stand at the precipice, intrigued by its enormity and dreadfulness.

13. Make the character in the poem do something he/she could not do in real life.

I dive like a heron, fishing in its depths for the panacea that will restore my soul.

14. Refer to yourself by nickname and in the third person.

Peaches desires more —ambrosia.

15. Write in the future tense such that part of the poem sounds like a prediction.

And the soul food she will soon get, but it’s not what she expects.

16. Modify a noun with an unlikely adjective.

Her just desserts have the gall to be simultaneously acidic and sweet. The second time around, the tequila feels more like a prison than an escape.

17. Make a declarative assertion that sounds convincing but that finally makes no sense.

Atlas reborn, she carries a burden that is far too heavy for her to bear.

18. Use a phrase from a language other than English.

Mi familia es mi fuerza y mi debilidad -my family is my strength and my weakness.

19. Personify an object.

The bottle gazes up at her from the floor.

20. Close the poem with a vivid image that makes no statement, but that echoes an image from earlier in the poem.

My Second Draft (Untitled)

My father is a rock. He is strong, stable, and enduring.

My family stands trapped, smiling behind the glass.

The jagged shards are sharp, threatening to cut me and the irony is not lost on me. Holding up the frame to my nose, it smells of old and the figures behind the cracks are quiet and stock-still.

I could almost taste the film of dust around its edges.

The Payton of San Antonio is not the Payton of Oklahoma City, though she takes their riverwalks with her.

My father is crumbling.

My mother is fluid like a river, taking up the shape of any container she occupies.

Some would call her flexible, others call her flakey.

I’ve made it this far without a mother, I must be fine without her.

She was just ‘round the corner. Just ‘round the corner.

The fathomless abyss of my childhood trauma gapes before me.

I stand at the precipice, intrigued by its enormity and dreadfulness.

I dive like a heron, fishing in its depths for the panacea that will restore my soul.

Peaches desires more —ambrosia.

And the soul food she will soon get, but it’s not what she expects.

Her just desserts have the gall to be simultaneously acidic and sweet. The second time around, the tequila feels more like a prison than an escape.

Atlas reborn, she carries a burden that is far too heavy for her to bear.

Her family watches her, sip after sip, frozen behind the glass.

Mi familia es mi fuerza y mi debilidad -my family is my strength and my weakness.

The bottle gazes up at her from the floor.

A photo of the poem “Trypophobia” in a two-page spread from pages 19-20 of the chapbook, Stories For The Road: Trauma and Internal Communication, Vol. 1. sitting on a brown wooden coffee table. Photo by Payton Hayes.

After I wrote the first draft, I left my poem alone for a few weeks so I could come back to it with fresh eyes. I chipped and chiseled away at it, cutting phrases in some lines and adding new thoughts in others. As I drafted this poem, its core message gradually became clearer with each new iteration.

Trypophobia by Payton Hayes

My father is my rock. He is strong, stable, and enduring—a stone statue against the dawn.

I stare at the relic of a bygone family—shattered, they stand trapped, smiling behind the glass.

The jagged shards are sharp, threatening to cut me open and the irony is palpable.

Holding up the frame to my nose, it smells of old and the figures peering through the cracks are motionless, silent.

I could almost taste the film of dust around its edges.

The Payton of San Antonio is not the Payton of Oklahoma City, though she takes their riverwalks with her.

And now, my father is crumbling.

My mother is fluid like a river, taking up the shape of any container she occupies.

Some would call her flexible.

Others call her flakey.

I’ve made it this far without a mother, I must be fine without her.

She was always just ‘round the corner, just ‘round the corner.

The fathomless abyss of my childhood trauma gapes before me.

I stand at the precipice, intrigued by its enormity and dreadfulness.

The liquid gold calls out to me, inviting me in with a false sense of courage.

I dive like a heron, fishing in its depths for the panacea that will restore my soul.

Peaches desires more—ambrosia even.

And the soul food she will soon get, but it’s not what she expects.

Her just desserts have the gall to be simultaneously acidic and sweet.

The second time around, the tequila feels more like a prison than an escape.

Atlas reborn, she carries a burden that is far too heavy for her to bear.

Her family watches her, sip after sip, frozen behind the glass.

She is swallowed up by the pit.

Mi familia es mi fuerza y mi debilidad—my family is my strength and my weakness.

The bottle gazes up at her from the floor.

(Hayes 2022, 19-20)

As you can see from all the examples above, Jim Simmerman’s “Twenty Little Poetry Projects” Writing Exercise provides an excellent framework for writing poetry. When you follow this process step by step, you end up with at least twenty lines of creative writing to serve as the foundation for a truly powerful message and concrete poem.

You may not necessarily keep them all or keep them in order. But surprisingly, this structured writing exercise allows creativity to flow freely. Once you have the rough draft, you can rearrange lines and edit the poem to your liking. I always enjoy working with this exercise and if you try this exercise or any of the other exercises in the book, please let me know what you think of it in the comments! If you want to find more amazing poetry writing exercises, consider picking up a copy of The Practice of Poetry: Writing Exercises From Poets Who Teach by Robin Behn and Chase Twichell from the links below or checking out a copy from your local library.

If anyone can find the webpage with Margo Roby’s post with her process on the exercise and poem, “A Thousand and One Nights” in Lunarosity, or information on the 2004 edition of Lunarosity, please let me know!

Bibliography

Hayes, Payton. “Angel” Pegasus XXXVII. Midwest City, O.K.: Rose State College, 2018. (Page 61).

Hayes, Payton. “A photo of the book The Practice of Poetry: Writing Exercises From Poets Who Teach, by Robin Behn and Chase Twichell on a wooden coffee table.” March 18, 2025.

Hayes, Payton. “A photo of page 61 of Pegasus XXXVII with the poem ‘Angel’ by Payton Hayes.” March 18, 2025.

Hayes, Payton. “A photo of the poem ‘Trypophobia’ in a two-page spread from pages 19-20 of the chapbook, Stories For The Road: Trauma and Internal Communication, Vol. 1. sitting on a brown wooden coffee table.” March 18, 2025.

Hayes, Payton. “A sideways photo of the book The Practice of Poetry: Writing Exercises From Poets Who Teach, by Robin Behn and Chase Twichell on a wooden coffee table.” March 18, 2025 (Thumbnail photo).

Hayes, Payton. “Trypophobia” Stories For The Road: Trauma and Internal Communication, Vol. 1. Edmond, O.K.: The University of Central Oklahoma, 2022. (Pages 19-20).

Roby, Margo. “A Thousand And One Nights” Lunarosity, 2004.

Roby, Margo. “A Thousand And One Nights” Margo: Roby: Wordgathering. (Blog).

Simmerman, Jim. Robin Behn and Chase Twichell, eds. “Twenty Poetry Projects” The Practice of Poetry. New York, N.Y.: First Collins Reference, 2005. (Pages 119-122)

Further Reading

You can also check out a copy of The Practice of Poetry: Writing Exercises From Poets Who Teach Read through your local library with apps such as Overdrive, Libby, Libro.fm, Borrowbox, Hoopla, or you can purchase an e-book or audiobook through Google Books, Audible, or Kindle.

Related Topics

Experimentation Is Critical For Creators’ Growth (In Both Art and Writing)

How To Write Poems With Artificial Intelligence (Using Google’s Verse by Verse)

Writing Exercises from Jeff Tweedy's Book, How To Write One Song

“Twenty Little Poetry Projects” Writing Exercise by Jim Simmerman

Why Fanfiction is Great Writing Practice and How It Can Teach Writers to Write Well

Screenwriting for Novelists: How Different Mediums Can Improve Your Writing

Recent Blog Posts

Written by Payton Hayes | Last Updated: March 18, 2025. Know The Rules So Well That You Can Break The Rules Effectively

“Know the rules well, so you can break them, effectively.” -Dalai Lama XIV

“Know the rules like a pro so you can break them like an artist” -Pablo Picasso

These are just two quotes that touch on the subject and since they’re from world renowned individuals, I think they must hold some weight. I think this notion of knowing the rules so you can break them holds especially true for the art of writing. Good writers who break the rules well are like the little blades of grass that peek up through the cracks in concrete—they shouldn’t be able to grow, they shouldn’t have the strength on their own to push through concrete—but they do, and sometimes, those weeds become flowers.

Whenever one of my writer friends says “You shouldn’t use adjectives” or “You shouldn’t waste too much time on mundane activities” what always comes to mind are two of the greatest fantasy writers of all time—J.R.R Tolkien and George R.R. Martin. They constantly break these two rules and many more in their work and not only do they get away with it, the are celebrated for it, which makes most writing advice out there, somewhat invalid. If they can do it and become world-class writers despite these common writing mistakes, why can’t I?

This is where knowing the rules comes in. If you know the rule, why it’s a rule, and why so many people tell you to steer clear of it, you then know how to use it to your advantage. The reason is, by knowing the rule inside and out, and knowing your writing is good, simultaneously, you know that you’re breaking the rule effectively.

Tweet from @PageTurner on Twitter.

If you break the rule in a bad way, like opening a scene with someone waking up and the following scene being predictable, then knowing the rule is pointless. But if you know the way you’re breaking it is interesting, unique, effective, and enhances or enriches the story, then not only are you breaking it well, you doing it in a way that will make other writers wonder how you got away with such a writing crime.

James Patterson opened up his bestselling novel, Maximum Ride with the main protagonist waking up, but he jumped right into the action in a fast-paced, and tense scene immediately after that kept readers engaged, enthralled, and made other writers wonder how he managed it.

Likewise, Tolkien went on for several chapters in the Lord of the Rings before the adventure ever began. One whole chapter even describe the dealings between the Bag-End Baggins hobbits and the Sackville Baggins hobbits, and spent another chapter describing a wordy, convoluted scene where Frodo and his friends enjoyed tea from and spent time with Farmer Maggot. Many writing coaches would say to avoid these lengthy scenes and cut them out since they didn’t drive the story or add to the plot in any way.

However, they’ve remained in every edition since publication and the novels are still celebrated today. It just goes to show if you know the rule like the back of your hand, you know you can break the rule and not only get away with it but be recognized for your writing when it’s done effectively.

For further reading on this topic, check out Steven Jame’s “Story Trumps Structure: “How to Write Unforgettable Fiction by Breaking The Rules” to:

Ditch your outline and learn to write organically.

Set up promises for readers—and deliver on them.

Discover how to craft a satisfying climax.

Master the subtleties of characterization.

Add mind-blowing twists to your fiction.

And that’s it for my hot take on how you can break the writerly rules by knowing them inside and out! What do you think about breaking the best-known rules in the writing world? Let me know in the comments below!

Thumbnail photo by Payton Hayes.